PROJECT ON SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN ARCHITECTURE

TBA is honored and very grateful to have received a 2023 ACTIVATE grant from AIA North Carolina to fund the launch of the PROJECT ON SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN ARCHITECTURE. The generous funding will provide for many of the start-up costs required to get the project up and on-line.

Thanks to AIANC, and especially to my home section of AIA Asheville who helped me get the funding request together!

More about ACTIVATE here

CIVIC SHEDS X 2

Work on the Civic Sheds project has continued through the spring. It was presented for a poster session at the 2023 Clemson University Research Symposium on 10 May. The notion of Design as Research is one that is evolving and generally recognized as a distinct method of research but colleagues in STEM fields doing “hard research” still have to work a bit to get their heads around our approach. Nonetheless, it was an honor to have the poster accepted for inclusion.

And yesterday I presented the project at the May Section meeting of AIA Asheville. Which, I realized driving up to Asheville from Six Mile, marked a kind of closure of a big meandering loop. I transferred my affiliation from the AIA Chicago to AIA Asheville when I came down, but I’d not been up in front of the section before. From sweeping floors at Six Associates at seventeen to presenting Civic Sheds.

paean to a sketchbook

In 2005, when I was working in Paris, I began having difficulty finding the sketchbooks that I’d been using for years. Trips back to the US meant scouring Asheville, Connecticut, NYC or Chicago for shops still carrying them. Success was being able to buy two or three at a time. Since the supply seemed to be drying up I cycled through a range of other sketchbooks, even custom hand-made books, but nothing worked as well. Eventually I was able to find a reliable source and bought them in bulk. I likely have enough to see me through now.

Anyone who works with their hands has strong ideas about their tools. I’ve used many different sketchbooks since I started architecture school but one particular sketchbook has been where I think, and where I work, for years - especially during the decade abroad when I was in the field all the time. I’m attached to them in a way that’s hard to explain, but they fit my hand, my eye, and my brain.

I’ve filled thousands of pages in these books with drawings, sketches, collages, and text. And though many first pages note the joy of opening a new book at the beginning of a trip or project, I’ve never dedicated so much as a page to the sketchbook itself. So this is my paean to the HOLBEIN 33YT-1 MULTI-DRAWING BOOK - OF, 195 mm x 145 mm, landscape format, spiral-bound with brown covers and a brown ribbon tie. There are 28 pages of 80 lbs neutral pH paper (guessing hot pressed): recto has some bite, verso less. Made in Japan.

mode d’emploi

First step is to remove the red plastic label with Japanese characters inserted into the spiral binding. Then open the book to the first facing page and write name with month and year centered about mid-page. Strike a horizontal line a bit wider than name and below that add an address (to which a lost book could be sent).

Between the rear cover and the last page insert a Madonna del Buon Viaggio prayer card from the Tempio di San Biagio in Montepulciano. The same card is transferred from sketchbook to sketchbook. The prayer card dates from my first visit to Montepulciano and offers protection to the traveler, obviously.

Trim the doubtlessly frayed ends of the ribbon ties with very sharp scissors and dip them into a very small quantity of white glue, evenly coating the end. Place the sketchbook at the edge of a table with the ties hanging free allowing the glue to dry.

Check the wire spiral binding to be sure it’s smoothly wound, and that the cut and bent ends are neatly tucked back into the coil. Monitoring the wire spiral is an on-going project and is important to insure that handling the sketchbook doesn’t compromise the pages ability to turn freely.

In order to keep the book tightly closed when traveling avoid the ribbon ties. They’re perfectly fine for the studio, but not so great on the road since, even tied tightly, they allow the pages to slide against one another. Instead place a fat rubber band around the end just inboard of ribbons’ attachment slot. The rubber band should be small enough to hold tight but also fit over your left wrist - its parking place while working in the sketchbook.

If you use the sketchbook as a way of looking then it has to be available and it’s never more available than when it’s already in your hand. Best is to lay the sketchbook into your left hand open palm, spiral binding towards you, bottom edge sitting at your pinky’s first knuckle with your fingers then curling over the bottom. When walking your thumb lays along the back cover, the spiral is to the rear and the cover brushes your left thigh. After a long day of walking it’s nice to rotate the book 90 degrees with the open end down and then slip your fingers inside the rubber band and let the book dangle a bit in your hand.

Packing the sketchbook into a messenger bag or daypack requires some care. To avoid dinging the edges it should never be placed loosely in a large compartment. Ideally it would slide into a pocket or sleeve within the bag that is appropriately sized. It carries best vertically with the spiral binding topside. And it absolutely must be easily retrievable - as in a single move to a reach in and take it out. When traveling the challenge is to capture the immediate impression; having to haul the sketchbook out from somewhere means you’ll just take a foto with your phone. Which is probably even handier.

holding the sketchbook

The source of the greatest pleasure offered by the Holbein 33YT-1 is the way it opens up and finds its place in my hands - book in left, pencil (almost always a pencil) in right. It’s a smooth movement: book carried at arms length then pulled up across the body, right hand grabs the end and flips the book so that the heel of the left is covering the front cover fingers curled around the spiral. Right then slips off the rubber band as the left presses the back cover against your ribs and holds it with pressure from the wrist and underside of the forearm. Your left hand fingers are free now so the right hand slips the rubber band over the left wrist.

Right hand takes the book by the open end and the left slides so that the wire spiral is nestled into the palm’s fold, thumb laying across the cover. Right hand middle finger dives in at the middle and the right thumb then fans the pages to find the new blank one.

Holding the book now simply depends on what you’re drawing. Full landscape mode has the thumb and index pinching the recto with the lower edge of the verso wedged into the joint between the base of the thumb and index. After a while you can rotate your hand so that the spiral binding is laying along your palm which spans the gutter and with all five fingers curled over the top of the page. Hand span is enough to support both recto and verso.

Another option is to lay the box long the full forearm, palm behind, with thumb and pinky hooked over the recto. Maybe my middle finger can get to the end to stabilize but it’s not essential.

When drawing on only either recto or verso it’s best to fold the sketchbook open and back on itself - this is the real attraction of the spiral binding and why keeping it in good shape is key - no gutter and a stable platform. You can hold it either by thumb/pinky combination hooked over top and bottom edges or support the back with the heel and fingers hooked around the end. The book can be rotated hand without any real change in the grip.

You have to stand to draw in the field, drawings done sitting down are always lazy looking. Stand up, feet spread to shoulder width, weight evenly distributed, left elbow tucked into the body if possible. Then the right hand can work.

preferred marking media

Part of living in a sketchbook is eventually finding a way of drawing (and writing) that fits. I love pencils. They’re equal parts crude and highly refined. Crude because who takes a pencil so seriously it can’t be crushed into any number of modes. Refined because they are graded from extremely hard to super soft with each gradient having its own specific qualities. Just as a cellist could speak as much about the bow as the cello, I could write another paean to Faber-Castell SV Castell 9000 H. The H is on the hard side and means my drawings tend to be sharp but also very light - almost impossible to accurately reproduce.

But I also work at times in charcoal, oil pastels, and conte crayons. Once working with one type of tool that approach tends to fill a book. Some books are a mess with colored dust flying and drifting page to page. Or there are smears of oil pastels everywhere. I rarely watercolor or wash, though I like the idea of adding a wash of color once back in the studio. Something about the preciousness of the medium turns me off. Again, once into a rhythm whatever I’m doing will persist for a bunch of pages.

working backwards

The natural flow of work is to keep turning to fresh pages for each drawing but some of the most interesting sketchbooks are those in which I’ve run short of paper and had to work backwards layering drawing on drawings.

paste-ins

I avoid any kind of scrap-booking activity but each book will usually pick up a paste-in of something found or a sketch on loose paper. I’ve sometimes accordioned larger drawings into a book - probably from my days using the Moleskine accordion-fold books. It’s not unusual for yellow trace or portions of plots to get tipped in as well.

inclement weather

If you can be outside you can draw. Use the upper body to shield the sketchbook from rain or snow. If it’s cold out just don’t think about it. If it’s bitterly cold out then draw until you can’t hold the pencil any longer and go find a café to warm up. If it’s hot, draw from the shade.

finishing a sketchbook

Knowing when to terminate the work in a book is an on-going question that gets answered in any number of ways. Easy answer is when the sketchbook runs out of paper, or maybe out of space in the margins and backwards loops. But some books end when the project, trip, or idea is exhausted. And if a book simply sits unattended for too long it should be retired.

using sketchbooks

What is a sketchbook for? (when it’s empty)

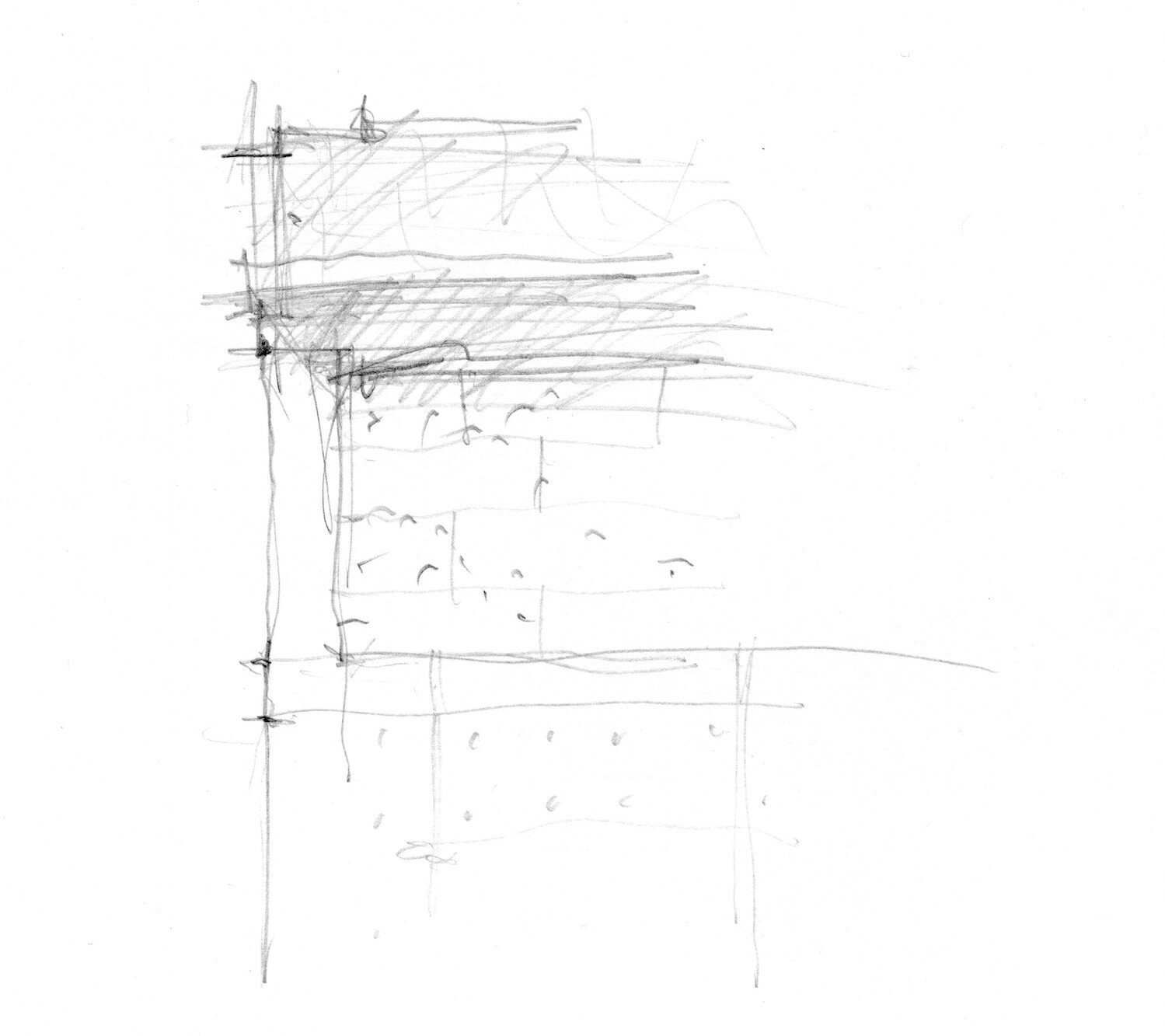

When working in the sketchbook I don’t make drawings. I don’t draw drawings. I have a lot of friends and colleagues who make extraordinarily beautiful drawings in their sketchbooks. But the sketchbook is my most important tool as an architect. I use drawing as a way of thinking and/or a way of seeing, as a pry bar to take things apart. It’s dirty messy work and how a drawing looks isn’t even in my mind as I draw. Composition and proportion of the drawing - utterly inconsequential. It’s a place to ask questions. The drawing is just a trace of a process as my eye and brain work together to figure a thing out. Specifically, drawing my way through a building or place is a way of getting that thing into my body so that the experience is a kind of sensory memory. All that matters is the doing of the work in the sketchbooks.

What is a sketchbook for? (once it’s full)

In one sense, as soon as a book is finished its work is done. If the work of drawing is a way of seeing and the drawings themselves essentially a remnant of an inquiry then the sketchbooks aren’t particularly important as things. The buildings and spaces we put into the larger built environment are the point. But the creative and critical work of design is a looping, intuitive, and reflective semi-process and revisiting older projects and field drawings almost always surfaces something new. At especially productive moments the eye and hand can by-pass the brain completely - drawings might include things that never even registered consciously. So re-opening a sketchbook is part of the critical work of re-thinking and re-working.

REVISITING LE THORONET

This past week I found a copy of the 2001 reissue of Lucien Hervé’s 1957 “Architecture of Truth” which was originally published as La plus grande aventure de monde. So I’m revisiting images of le Thoronet, Hervé’s and my own photos, in a rock house while listening to cicadas which were also the sonic background to my visit to the abbey in 2018 (cicadas are the soundscape to all of southern France). Most interesting, though not surprising, is that Le Corbusier wrote an introduction to the book. I’m looking for the original in French but the translation goes, “stone is man’s best friend; its necessary sharp edge enforces clarity of outline and roughness of surface; this surface proclaims it stone, not marble; and ‘stone’ is the finer word.”

As the pandemic was finally easing summer 2021, we booked a trip to France for most of July. After a few days in Paris and en route for Marseille, I decided to stop over in Lyon and visit le Couvent de la Tourette again. The site of my first architectural epiphany and the building from which I have probably learned the most about architecture. And which is so closely linked to la Thoronet.

On 28 July 1953 Father Marie-Alain Couturier wrote Corbu “J’espère que vous avez pu aller au Thoronet et que vous aurez aimé ce lieu. Il me semble qu’il y a là l’essence même de ce que doit être un monastère à quelque époque qu’on le bâtisse, étant donné que les hommes voués au silence, au recueillement et a1la méditation dans une vie commune ne changent pas beaucoup avec le temps.” Corbu had visited on 26 July making two drawings in his sketchbook that day. Critics are still arguing over Corbu’s synthesis of various influences; but the affinities between la Thoronet and Corbu’s work at la Tourette are clear.

Corbu wrote of la Tourette, “Mon métier est de loger les hommes. Il était question de loger des religieux en essayant de leur donner ce dont les hommes d’aujourd’hui ont le plus besoin: le silence et la paix. Les religieux, eux, dans ce silance placent Dieu.”

I had been prepared for a hot and dry summer in Provence, but not for the heavy rain that fell all that day in l’Arbresle. As always, I walked up from the l’Arbresle train station and was completely soaked through when I eventually came up the allée to the priory. Having been effectively baptized. The visit was constrained by time and the omnipresent docents so it was possible to see only the salle de lecture, oratoire, réfectoire and église. After the formal tour I was able to stay on another hour to draw. Not the visit I’d hoped for but enough until the next one.

NEW PROJECTS

The past year has been productive as three different ideas about projects that have been in a kind of gestational state for a long time developed into full-blown projects. The suspension of ordinary things due to COVID and more latitude as an academic this year allowed for the time and focus needed to solidify these ideas. All three projects come out of frustration at not finding what I assumed was out there somewhere already.

The Project on Southern Appalachian Architecture’s goal is to attempt to knit together a broad survey of what kind of work is going on to figure out the built environment around here. What have we made, what are we making, and what do we think about both of those?

The Civic Sheds Project extends speculative TBA design work done over the past few years into the public realm and should see the first Shed completed towards the end of the summer.

And finally, years of looking, drawing, and making built incursions in Mies van der Rohe’s building for the IIT College of Architecture - S.R. Crown Hall - have coalesced into the idea of a book-length exploration. It’s the most intimidating of the three projects since engaging with Crown via writing is very different than the other approaches.

And finally, getting the TBA website onto a more robust platform has been a long time coming. It required a gut renovation so it still needs some work rebuilding the portfolio and reformatting imagery. Coming soon.

TEACHING MASONRY

My role as coordinator of the second year studios at IIT and again at Clemson has meant that, along with teaching wood and masonry, I have spent a lot of time thinking about how to teach these materials to architecture students. This semester I’m teaching Structures I in the graduate program and these issues are back on the front burner. Which means I still spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about these materials in very basic terms. Wood, in all its variations, masonry, and especially stone.

And for reasons perhaps related to my many years buried in the stone cities and buildings of Europe, but also to something more significant, immediate, and powerful, I am haunted by stones. I dream of the taste and smell of certain stones. Though I'm a southerner, I never ate dirt, but I know well many and varied tastes of the rocks of the southern Appalachians. Even now I can summon the taste of rocks from the creek on our land in the Black Mountains.

I'm haunted by the image of Assisi's pink stone shifting colors under a hard rain. Firenze’s pietra dura and pietra serena. The Loire valley’s slate. And the color of Montepulciano’s San Biagio late on a July afternoon is one seared into my brain. I rock-climbed for years and can recall in hyper-detail the feel of rock on certain pitches around Asheville. The quality of friction provided by an outcropping on a particular face.

So finding this photograph recently was a kind of minor miracle. One because of the people in it. But also because of what it told me about things I didn't realize I had in me. My grandfather, my father, and my uncle at their rented house in Haywood County outside Asheville around 1937.

L’ABBAYE DU THORONET

My research and practice preoccupations have been, for some time now, centered on the work of Mies and contemporary building enclosures. And especially how Mies’ work informed and continues to influence our thinking about building skins. But as my interest in contemporary lightweight, multi-layered enclosures tracked alongside architects’ contemporary obsessions with fully glazed facades, architectural and environmental questions about the transparency mania have been harder to ignore.

A two-week stay in the south of France this summer allowed me to finally visit l’abbaye du Thoronet. It was the last building on my list of must-see/hope-to-sees. And in many ways an appropriate symbolic close to my architectural education. My first architectural epiphany occurred at Corbu’s le Couvent Sainte Marie de la Tourette while I was a grad student living in Genova. Since then I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time with significant buildings and places - thirty years of trips dedicated to seeing buildings, including a decade of full-time architectural travel while I was at IIT. So my visit to Thoronet was a remarkable sort of double full circle in light of Corbu’s deep interest in the abbey when he was working on la Tourette.

I’ve written of the pleasures of teaching masonry, especially to beginning students. Some of the wonder found in stone and brick is in their ability to speak so profoundly of place - of the local stone or nearby claybank. Today our masonry products ride in on the back of the warped economies of the building industry’s global logistics, meaning it can be cheaper to use stone from India than to use what’s available the next county over. But local masonry has an inherent capacity for tying a building into place - which seems to me one of the baseline objectives of what we do as architects. And an architecture of multi-wythe masonry is an architecture of mass. Mass as opposed to the multiple thin and differently performative layers of current wall systems. And an architecture of mass has in it the nearly forgotten space of poché.

So while one part of my practice interests is in thin-ness, the other is in Stanley Tigerman’s idea of material butter - the same inside as outside. Material all the way through the wall, the monolithic. The very idea seems helplessly retrograde. Although stacking and carving operations are fascinating as a building technique and the hand-sized units of masonry introduce possibilities for texture and variation, I find the technical simplicity of massive construction most compelling. And an architecture of mass tends to be inflexible; rapid reconfiguration of elements usually isn’t a design feature. I’m not making an argument for stability, fixity, or timelessness. I like that, though buildings can be loaded with sensors and actuators trying to react to my movements or anticipate my desire for a new carton of milk on the second and fourth Tuesdays of each month, there may be buildings to which, due to their intransigence, I have to react. Variously and continuously. Differently by season and over time.

It’s common to design lighting that has countless scenarios pre-programmed across a bunch of luminaires, controlled by a simple remote. But as I grow into architecture I find myself more enthralled by the ways sunlight through a window in a room structures where I do what I do, throughout the day, and by season. I’ve found that I prefer engaging with the building rather than being in a building reacting to my caprices by flashing LEDS at me, or making sounds.

I’m utterly unable to inhabit the world as an eleventh century Cistercian monk. Their world is unavailable to me, so the way of living in and using the complex of the abbaye is also unavailable. Today the abbaye is a French monument national and considered a historical site of cultural significance and could be seen as in caesura. Stilled by the power of the State. Outside the quotidian flux of the world. So we come to the remnants, the pieces that survived or were restored as people from another world entirely but people still capable of responding to the stone, the colors, the articulations of surface, and the light and its shadows. Absent the daily rhythms of occupation by the Cistercians and finding only a portion of the abbaye relatively intact, we’re left with a kind of stripped down, reductive version. Not pure and not essential - just minimized. But the reduction does eliminate a certain degree of static. Understanding the heaviness and thickness seems elemental, a kind of architectural lesson on fundamentals.

In a reversal that nicely doubles the circular nature of the visit, I came to the abbey via la Tourette whereas la Tourette, circuitously, arrived via Thoronet. During my time in Montepulciano I spent a lot of time at l’abbazia di Sant’Antimo, a Benedictine monastery below Montalcino in the val d’Orcia, so my expectations of Thoronet were informed. Somewhat. But I’ve spent weeks in la Tourette (much more time than I spent in Mies’ chapel at IIT) and it may well be one of the buildings I know best. So Corbu’s translations of Thoronet was the frame of my visit. I essentially came to l’abbaye du Thoronet carrying with me a 1950’s Dominican friary.

The project for le Couvent Sainte Marie de la Tourette came to Le Corbusier via his relationship with le Révérend Père Marie-Alain Couturier and after the project for Sainte Baume and the construction of the chapel at Ronchamp. Couturier wrote Corbu encouraging him to visit Thoronet. “Il me semble qu’il y a là l’essence même de ce que doit être un monastère à quelque époque qu’on le bâtisse…” Corbu visited the abbaye and though the specific relationships between his design for la Tourette and le Thoronet are unclear, it nonetheless carried immense weight in the development of the project.

Having dreamt of visiting Thoronet for so long, my visit wasn’t particularly easy. Arriving preoccupied with other concerns and, as always, being hemmed in by limited time and the exigencies of heavily visited tourist sites made for a hard segue from world to abbaye. After taking a few deep breaths, adjusting to the heat, settling into the landscape and making a slow walk around the abbaye time slowed. As occasionally happens, I never opened my sketchbook. The difficulty of climbing into that place right then was all I could manage. But simply moving through the spaces alternately hot and cool accompanied by the scent of lavender and the omnipresent sound of cicadas was a pure and ineffable experience only architecture affords.

It was transcendent.

And what has remained with me is the way in which the stone, monolithic and mostly unadorned, massive and heavy, vaporous and featherlight, cool from its weight and luminous as a surface, seemed to do everything at once. Enclosed, defined, enfolded, embodied massiveness, and held the secrets of void and hollow. In the end, confounding.

CHICAGO

The start of the trial of Laquan McDonald’s murderer today has had me thinking about Chicago. It took four years to get this case to trial and trying to understand why that is can make you crazy. I have had a long, close, and complicated relationship to this city. And the ways in which the city has left so many of its citizens behind and the manifold failures of government and policing often leave one in despair. Remedies and solutions, or simply justice, so often seem just unobtainable. It’s a hard city.

I arrived in 1988 as a graduate student entering the M.ARCH program at UIC and, despite spending the majority of my time now in the South, I have yet to leave Chicago. I realized many years ago that as deeply involved as I have been with Chicago I could never, and would never, consider myself a Chicagoan. I’ve lived a lot of places and I’ve been more attached to places I’ve spent little time in than I am to Chicago. As much as I love Chicago, I have never felt like I was home there.

But when Amanda Williams was at Clemson to give a talk last fall I realized something. In spite of my not being a Chicagoan, I am, absolutely and without a shadow of a doubt, a Chicago Architect. Chicago formed me as a practitioner and professional. And most importantly, as a citizen-architect. The issues Chicago faces are the issues that animate my approach to architecture. I see our role as architects to be inescapably bound up with the most serious concerns of our society today. Chicago taught me that. Stanley Tigerman was the first of many educators, architects, and peers who showed me how we might conduct ourselves.

In spite of the horrible pain I often feel being so tightly bound into this maddening magnificent city, I am very proud to say I am a Chicago Architect.

21 January 2019 postscript: the Chicago police officer who killed Laquan McDonald was sentenced to 81 months in prison and three fellow officers involved in the cover up went free (for now).

DRAWING AS THINKING

Over the past few years I've explored a lot of ways to more easily grab fleeting thoughts, sketch, draw, capture images, and develop ideas whether drawing or writing. And although the digital toolbox allows for multi-media inputs, post-production manipulations, advanced searching, and relatively safe storage, none of the gadgets or apps I've come across answer to my larger concerns, or desires. And none of them are actually that much fun. So I find myself coming back to my sketchbook whenever I'm working.

There's a way that drawing by hand on simple supports like paper provides for some connection between thought and expression that's fluid and virtually frictionless. I became an architect drawing and thus thinking by hand, and maybe that facility provides for this sense of souplesse. I'm not sure that the sketchbook would be as useful without a lot of time working in a sketchbook. But it seems to me that there are parallel routes towards an idea: one is thinking through drawing and the other is thinking through making. I don't consider making drawings to be the same a working by drawing. There are a lot of practices aimed at making drawings that look like drawings - the glorious travel 'sketch' is one of those types. I'd propose instead a way of drawing that doesn't aim to produce the sort of sketch that's carefully composed, well-proportioned, and, in short, beautiful. The drawing practice I have in mind is more like the use of a wrecking bar - it's a demolition tool. Drawing can be a way of taking an idea or a thing apart. It's ugly and messy and the residue isn't something anyone wants to see. But it's an extraordinary method of attack. I'd consider many of Michelangelo's sketches as examples.

Just ahead of the fall semester's launch a couple of years ago I went down to spend a weekend at the Kimbell. Two days of drawing, looking, and thinking. Filled a couple of sketchbooks and just sort of disappeared into Kahn's work for hours at a time. I sometimes think spending a decade in Europe in and around some of best buildings in the world taught me about architecture. Maybe, but the byproduct of looking hard at architecture for a decade was learning how to think through drawing. And the habit of interrogating buildings, like the Kimbell, with a pencil and sketchbook has the same smooth flow of idea and inquiry that is design.

GROUND-BREAKING

Monday ground-breaking for a small project in Lakeview revealed beautiful white Lake Michigan sand about 36" down. All the mythical and poetic qualities which surround the act of opening up the earth were that much stronger in light of this remnant of the prehistoric edge of Lake Michigan.

I'm as impressed as most any architect by the fairface finish concrete Ando and other folks can sometimes pull off. That feat speaks of planning, good specifications, good concrete mixes, and proper placement. An ultimate test for control freaks since the task is, in essence, to make a silk purse out of a sow's ear. But that's about surface and touch and cosmetics and silk purses have only limited appeal for me. The notion that architectural concrete's real character is expressed in the close control of surface finish elides the real power of this material.

So it has always seemed very odd to me that the part of the structure that connects to the ground, the building element that conveys all the above-grade structural gymnastics to the earth itself - the footing - is utterly ignored materially and conceptually. Architects typically don't even bother with drawing foundations, leaving that work to the engineers' standard details. Foundations, and particularly footings, disappear from sight so how they're made, their form and their finish, is irrelevant. The only important material qualities involve placement, cost, ultimate strength, and permeability. In NC we seldom even bother with formwork for footings; trench and pour.

Yesterday the concrete crew poured concrete footings atop this extraordinarily white prehistoric Lake Michigan sand at this small project in Lakeview. And I wondered what it would mean to exercise the care usually reserved for making concrete walls look a certain way to making the bottom face of the footing - the place where all we do above travels downward in a kind of exquisite chthonic embrace. Our best face towards Terra.

DR MARTIN LUTHER KING JR NATIONAL MEMORIAL

The lukewarm to negative reviews of the newly dedicated memorial and yesterday's celebration of Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday made me think about our competition entry for the memorial in 2000. From our submission (see the work tab for project images)

Our proposal calls for extensive fill thereby raising the ground level along this same line to a high point of 5m near the site’s centroid, thereby effectively inverting the site’s “natural” declination. From the new rise the fill then tapers to the northern and western confines while forming an embankment falling to a long retaining bench backing a traprock paved surface which echoes the arc of the basin’s edge and the grove of cherry trees. The two significant structures and the major hard surfaces are, consequently, peripheral leaving the large central grassed area programmatically vacant. The resulting topography and evacuation of programmed use-space at the site’s center serves to slough off the obsessively cast network of axial delineations and suppress the normative centripetal monumentalism of Washington. Two continuous rows of tall, fragrant loblolly pines, one running along Independence Drive and another along the western access road to the define the memorial precinct. A row of low dense crab apple trees parallels the loblollies on the west while an existing stand of dogwoods will remain along a section of Independence.

We are proposing two structures; the first of which is a trellis made of lightweight steel and skinned pine poles, planted with wisteria, that runs along the entire northern edge filtering, with the adjacent loblollies and dogwoods, the movement and traffic noise on Independence while providing for views south across the site to the tidal basin. The second structure, covalent to the trellis, is a low ribbon of very large and solid sections of cast glass running north to south along the western side of the site for its entire length. Embedded within the glass block castings are display screens for video and film programming.

The majority of visitors will encounter the opalescent glass structure entering into the memorial after passing beneath the line of loblollies. The low, wide run of cast glass, a translucent horizontal counter to the massive vertical opaque materiality of the surrounding monuments, is illuminated by the evanescent video and film images being shown on the embedded screens. The glass sections will be cast off the ground at particular sites that carry great significance to the historical narrative of the movement, thus commemorating in a quiet way its origins in the “local” and the fugitive immediacy of “place”.

As always, not winning was a disappointment; but in this case it was doubly so since the winning scheme was a mostly stale idea about a monument - not a memorial.

DOUG GAROFALO

Word came this morning of Doug Garofalo's death on Sunday. And all the light immediately drained from what had been a pleasant summer day. The sad reality of his absence has just grown more insistent in the hours since. Chicago has lost one of its kindest, most generous and best architects. We've also lost the most gracious person I've ever known.

I first met Doug in New Haven when he was a finishing his Masters at Yale, and met him again a few months later here in Chicago at UIC where he had just started teaching and I had just started studying. He was my professor, my adviser, later a collaborator, and then a colleague and friend. I've never known anyone like Doug. I doubt I will again know anyone like Doug.

Now, as the hours pass and the news slowly assumes its brutal outlines, contemplating a world without him means having to accept a world that will have a little less color, less delight; a world missing some great portion of thoughtfulness, one where wonder is less available, and worst of all, one that is a lot colder.

BURNHAM PRIZE: MCCORMICK PLACE REDUX

The Chicago Architectural Club is pleased to announce the 2011 Burnham Prize Competition: “McCormick Place REDUX”. This year’s competition is co-sponsored by the Chicago chapter of the American Institute of Architects and Landmarks Illinois and is intended to examine the controversial origins and questionable future of the McCormick Place East Building, the 1971 modernist convention hall designed by Gene Summers of C.F. Murphy Associates and sited along the lakefront in Burnham Park.

Built on parkland meant to be “forever open, clear, and free”, considered an eyesore by open space advocates, and suffering from benign neglect at the hand of its owners, the Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority, Gene Summer’s design for McCormick Place East is nevertheless a powerfully elegant exploration of some of modernism’s deepest concerns. The current building’s predecessor generated withering criticism from civic groups so when it burned in 1967 its critics mobilized. The raw economic power of the convention business served to hasten rebuilding atop the ruins. But while Shaw’s previous building lacked any architectural merit, Gene Summers brought to the new project his years of experience at Mies van der Rohe’s side. The resulting building is a tour de force that succinctly caps the modernist dream of vast heroic column-free interior spaces.

The competition charge:

The Metropolitan Pier and Exposition Authority claims the building needs $150 million in improvements and that the building is functionally obsolete, too small to remain viable as an exhibition hall. While the facility appears frayed, the building is in fundamentally sound condition. Connected to the larger McCormick Place exhibition complex by a covered bridge over Lake Shore Drive, the stronger connections are to the lakefront, the museum campus and nearby Soldier Field. Surrounded by an over-abundance of parking, served by CTA buses, and bordering the immensely popular lakefront walking/running/biking path, the possibilities for the building and the site would seem boundless. But so far, the only visions for its future to be expressed publicly been total erasure or reuse as a casino.

The “McCormick Place REDUX” competition seeks to launch a debate about the future of this significant piece of architecture, this lakefront site that was effectively removed from the public realm, and the powerful pull of a collective and public claim on the lakefront. This iconic building is caught in the crossfire of a strong, principled, and stirring debate. So the question posed by the competition is quite simple: what would you do with this massive facility? What alternate role might the building play in Chicago should it be decommissioned as a convention hall? And if the building were to go away, how might the site be utilized? What might you do with a million square feet of space on Chicago’s lakefront (along with 4,200 seat Arie Crown theatre)?

Clearly outmoded for its original use, sited on a spectacular stretch of lake-front, and undoubtedly of very significant architectural quality - what visions are there for a resolution?

Link to competition website is here

REYNOLDS PRICE

A fellow North Carolinian, the writer Reynolds Price, died today at the age of 77. According to the news reports he died of complications from a heart attack he suffered Sunday.

He said once, of Macon North Carolina, “I’m the world’s authority on this place. It’s the place about which I have perfect pitch.”

I can't think of a higher calling for an architect than to be the world authority on some place. I love the idea of having the perfect pitch of a place. I asked Stanley Tigerman for some advice as I was about to finish grad school and he said that to be an architect you had to go someplace and stay put there for 50 years - then you maybe could figure it out. I think I've finally come to understand what he meant by that.

MOSE AND IUAV WS09

We've nearly finished the text for the IUAV WS09 publication. Thanks to Luca Mezzalira and Vittorio de Battisti Besi for helping smooth the piece into a much better Italian than I could manage alone.

La Sfida del MOSE

Il programma proposto per il workshop si fondava su due principali idee: la prima è quella di considerare un workshop estivo di tre settimane simile ad un’avventura in cui direzione, energie necessarie e risultati sono totalmente imprevedibili; la seconda consiste nella volontà di considerare le più complesse questioni in architettura le quali, all’interno dell’esplosivo potenziale di un workshop estivo, possono divenire un mezzo ideale per un’indagine approfondita.

Il mio lavoro si sviluppa tendenzialmente in due direzioni: progetti su vasta scala e progetti di dimensioni molto contenute. Abbiamo recentemente proposto un parco lineare di 4,5 km di lunghezza nell’area nord-ovest di Chicago e un centro civico di 2.500.000 metri quadrati in prossimità del Midway Airport. La stessa modalità di lavoro vale per i progetti che ho sviluppato negli ultimi anni attraverso il mio insegnamento all’IIT. Progetti molto grandi o molto piccoli. Venendo a Venezia eravamo preparati a pensare in grande. E nel centenario del progetto di Burnham per il piano di Chicago, potremmo dire che the pump was primed.

A Chicago abbiamo visto recentemente completato un enorme progetto denominato Deep Tunnel. Si tratta di una riserva sotterranea per la raccolta delle acque meteoriche che si estende per 175 chilometri e può raccogliere fino a 60 miliardi i litri d’acqua. Il tutto è praticamente invisibile. L’unica cosa che si vede è quello che non accade quando cadono le consuete piogge torrenziali di fine estate: la presenza del Deep Tunnel ha portato ad avere cantine asciutte e un immenso buco nel bilancio pubblico. Il Progetto si è concretizzato nell’eliminazione delle inondazioni e nell’evaporazione di montagne di soldi.

Il nostro interesse per il MOSE dovrebbe essere evidente. Faraonico nella scala, sconcertante per la quantità di materiale necessario, terribilmente oneroso. Il MOSE è all’apice nella lista dei progetti a vasta scala in fase di realizzazione nel nostro pianeta, un progetto che sta ridisegnando in modo dirompente il delicato paesaggio lagunare. Le infinite controversie, i seri dubbi sull’effettivo funzionamento del progetto, i costi immani e l’impatto sull’ambiente che caratterizzano questo progetto sono elementi dai quali scaturiscono i nostri sforzi per ri-modellare il mondo. Ma nonostante l’intensità dello sforzo la parte visibile, tangibile, del progetto, la sua manifestazione fisica è sostanzialmente invisibile. Come nel caso del Deep Tunnel il suo eventuale successo sarebbe dato, semplicemente, dall’assenza dell’acqua alta.

Quindi la domanda che ci siamo posti durante il WS09 era se l’architettura fosse o meno in grado di partecipare alla concretizzazione di questo progetto ambizioso. O se il compito che le compete è soltanto quello di provvedere poi all’aggiunta di elementi decorativi, di aggiungere piccole finiture a progetti già definiti dalle grandi compagnie investitrici. I tanti programmi One Percent for Art fanno sorgere una semplice domanda: perché l’1%? Perché non 50%? Perché non un livello di parità? 100% per l’arte? Sei miliardi di euro per un’opera pubblica…e allora perché non sei milioni di euro per portare alla luce il progetto?

La sfida proposta ai 40 studenti che hanno partecipato al workshop era trovare un modo per rendere visibile questo vasto progetto, quasi completamente invisibile. Che il MOSE venga ultimato o meno, che esso funzioni effettivamente come è stato immaginato o che aggravi la situazione, non rientra nelle nostre preoccupazioni. Noi abbiamo affrontato il progetto nelle sue ambizioni, invadenza, e nella sua scala.

Il nostro insegnamento al workshop è consistito prevalentemente nel sollecitare un ragionamento ad una scala appropriata a quella del MOSE. I primi ragionamenti progettuali degli studenti erano fossilizzati a modelli tipici della Venezia storica, ad una scala di super-dettaglio più adatta forse ad una piccola costruzione in campo San Polo. Una torre veniva considerata “alta” ad appena 30 metri, gli spazi aperti verdi venivano chiamati grandi anche se solo di un ettaro.

Durante le discussioni con gli studenti l’obiettivo era quello di ragionare in termini spaziali all’interno dei 550 chilometri quadrati della laguna, con un budget di sei miliardi di euro.

CIMITERO DI LONGARONE

In spite of the years I spent living in Italy and hunting up significant buildings, I still occasionally stumble upon work of astounding beauty or power that is completely new to me. While in Venezia this past July, my friend Adolfo Zanetti took me up to see the Giovanni Michelucci church in Longarone, built to commemorate the Vajont disaster (nice church but nowhere near as unsettling as the Chiesa della Autostrada near Firenze). And then we went to see the town cemetery, a project Adolfo knew of (he studied with Tentori) but hadn't ever visited. So I didn't get much of a run-up as we approached. Generally worn out from the IUAV workshop and already looking forward to dinner at Adolfo's parents, I wasn't particularly alert as we wandered in. But what followed was a kind of rapid on-set euphoric experience as I quickly came alert.

Designed by Gianni Avon, Francesco Tentori, and Marco Zanuso, the cimitero di Longarone was built between 1966 and 1972. It's one of the best works of the period I've seen in Italy, and can match about anything I've seen anywere.

I'm still at a loss to describe the experience coherently, but my impression was of a long sinuous crevice cut into the ground plane and running away from the entry gate on an slight angle against the slope's fall line. The cut is retained by a series of walls in rough local stone and wanders through a range of exquisitly proportioned spaces and rooms. At the top of the wall, which appears to be the natural grade, grasses and other plantings run riot covering the seam. Just back from the edge the grass is mown like a rich carpet.

The view sweeps out over the 100 meter long expanse across the valley and to the opposite mountains. At your back is the mountain. There's a chapel at the gate and a large above-ground mausoleum at the head, but the sense is that the project is scored into the earth. Not unlike Carme Pinos work at Igualada.

My first thought, overpowering in its force, was this is where I would like to be buried. Second thought was peccato, non si riesce. Third thought was forgot both the camera and sketchbook. Of all the work I saw this summer, this is the place that continues to haunt me. Most of the work I do, and all of the work I do with students, poses the same basic and simple question - is architecture a viable form of cultural expression today? In this place I think I could say the answer is more likely yes than no.

IUAV WORKSHOP

IUAV WORKSHOP 09

Three weeks of very intense activity will end today with mounting the final exhibition. The students bore down this week and from cursory glances at the final boards as they filed through in the print queue I'd say the final projects will be very strong. We're in Aula 2.2 Magazino 6 - top floor over-looking the Giudecca canal. There should be a sort of vernissage this evening but the exhibtion opens tomorrow officially. All that remains for the larger Workshop 09 program is the reception at the director's house and a very big and rowdy party on the beach tonight.

The idea for the workshop "La Sfida del MOSE" came out of an on-going interest in infrastructure projects. I brought a very simple question (one I have been asking for some time) to the workshop: can architects contribute in any meaningful way to projects whose scales radically outstrip our normal, or traditional, range of operations? Several architects from IUAV have been working with the Consorzio Venezia Nuova on small pieces here and there - a control tower, tool sheds, whatever. Considering the scale of the project these are barely bread crumbs. Do we have the range to stretch out to the scale of this project without playing at being city planners? Are there skills and insights we can deploy across the breadth of such a complex project, or are we doomed to the 1% for art allocation?

Like the Deep Tunnel project under Chicago, MOSE will absorb billions of euros but remain virtually invisible. The success of both projects measured by what doesn't happen in a successful deployment. The eventual delivery of the project will in many ways squelch the endless debates over the operation. There were few public polemics concerning Deep Tunnel, but MOSE has been and remains extremely controversial. The project is not supported by the current Venice city administration. So the WS09 project charge is direct: render the MOSE project visible. The physical manifestation of the project (gates, jetties, locks, technologies and techniques), but also the debate, history, massive operational programs, and obviously the costs.

Based on our work here at IUAV and my project last semester at Midway Airport, I would suggest that there might very well be space for us to work at this immense pharaonic scale.

Time for thanks: first to the IUAV administration for the invitation to participate in the WS09. Second to Prof. Luigi Croce for securing that invitation and offering up his house, Luca Mezzalira my assistant from IUAV who was the most critical element in the entire endeavor, and finally to the students themselves - siete bravi ragazzi, sono contento avere l'oppotunita per lavorare con tutti voi. Vi Ringrazio.

jean nouvel’s quai branly

Getting close to the summer Paris program's end now and the range of work we won't see is daunting. In spite of an ambitious agenda and the group's noteworthy stamina. One month in Paris simply isn't enough to do much more than conduct a quick survey. But I recall saying the same thing when I was running the semester-long programs here. In fact, four months was about right to develop some familiararity with Montepulciano, not a very big place.

Last week we were at Jean Nouvel's Musée Quai Branly. It was my second visit since it opened and the most striking change was the greater density of the plantings. Now there is some sense of the potential for the buildings to recede somewhat into the gardens’ lush landscaping. This second visit also reinforced several of my earlier less-positive impressions.

One is that Nouvel seems to have been trying very hard to provoke some stale and generally inert body into a reaction against the idea of a free-wheeling architecture. Trying really hard. The plethora of materials, the long elaborate entry sequence, and the general exuberance that may somehow symbolize youthful energy. I find the museum to be a fairly strong project and one that succeeds on most of its terms (especially in integrating landscape and architecture). But the feeling that we should somehow be scandalized persists. I’m not even sure who the stand-in for the stale body would be since the museum was pretty lavishly funded by the state and benefits from official sanction via every imaginable channel. Nonetheless, the driving force of the design would seem to me to be a tantrum of sorts; even though no one said little Jean couldn't have the ice cream cone.

The other impressions I recall had to do with the interiors mostly. The theatricality serves the individual objects well but its relentlessness begins to dull the overall reception of the extraordinary collection. I felt as if I was in a Disney version of what an anthropological museum should be. Worst of all is the pervasive darkness. Naturally, one needs very low levels of ambient light to create the dramatic spotlighting of the objects under glass, but after two hours I was dying for some light. I wondered if the hanging boxes were meant to be light controlled but the area devoted to displaying light sensitive objects ate the entire floorplate. Finally, I just can't understand the French love of tiny, packed, airless museum spaces. Too much beautiful work badly crammed into too little space, jammed with too many people, and filled with warm, humid, very stale air.

RENZO PIANO IN CHICAGO

First visit today to see Renzo Piano's Art Institute addition from the inside. First impression was light, then space. For those of us here in Chicago I think it's hard to see the project yet outside the context of the immediate past. The entry point into the new wing is in what was one of the Art Institute's most unlovely corners. It has been even more depressing in the interval without the Chagall windows. But now one looks north into the spacious atrium filled with natural light and the effect is very nearly breathtaking. (The upper level entry is off the odd balcony fronting O'Keefe's cloudscape and does not work so well.) So the spaciousness and flood of natural light is a real departure from the other parts of the building.

What strikes me, while my impressions are still fresh, is the measured and relatively modest character of the addition. The Art Institute is a messy complex and Piano has not made sense of it, nor given it an identity strong enough displace the Michigan Avenue entrance. That would probably be an exercise in futility. But he holds the NE corner and cements the eastward relationship to the park. The connection to the north is fine especially in framing Gehry's project, but the key adjacency is to the east. That works very well.

I see the addition as fitting into the tradition of seriously competent buildings in Chicago. The AI publicity mill's hype and high expectations clearly surpassed what is actually a very modest building. The care taken in developing the building's systems counts for a lot. My sense is that Piano has delivered a building we can appreciate and one that isn't less for being something less than stellar. And as I get more and more bored with the slew of buildings straining for an iconic presence, deep competence is ever more engaging.