paean to a sketchbook

In 2005, when I was working in Paris, I began having difficulty finding the sketchbooks that I’d been using for years. Trips back to the US meant scouring Asheville, Connecticut, NYC or Chicago for shops still carrying them. Success was being able to buy two or three at a time. Since the supply seemed to be drying up I cycled through a range of other sketchbooks, even custom hand-made books, but nothing worked as well. Eventually I was able to find a reliable source and bought them in bulk. I likely have enough to see me through now.

Anyone who works with their hands has strong ideas about their tools. I’ve used many different sketchbooks since I started architecture school but one particular sketchbook has been where I think, and where I work, for years - especially during the decade abroad when I was in the field all the time. I’m attached to them in a way that’s hard to explain, but they fit my hand, my eye, and my brain.

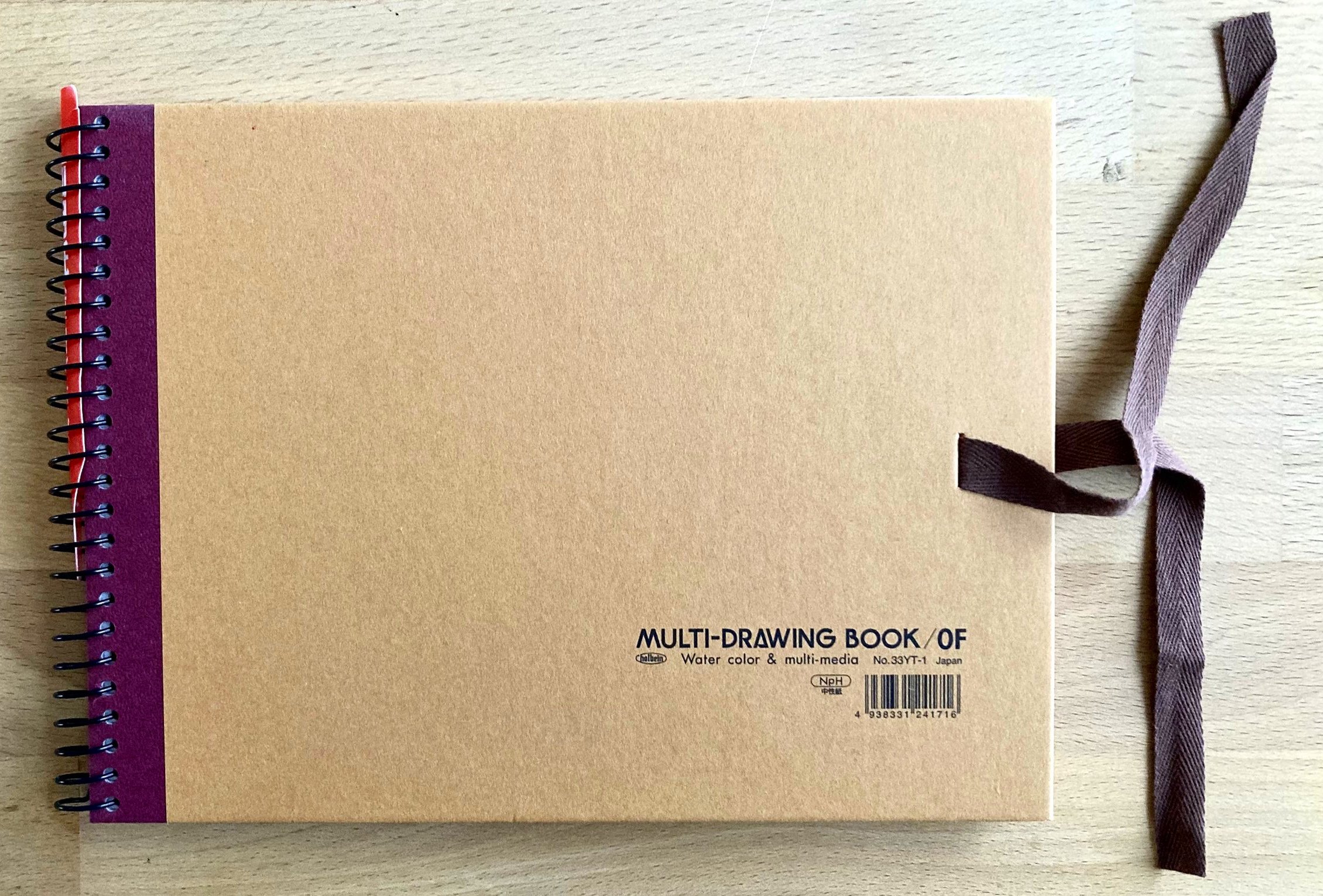

I’ve filled thousands of pages in these books with drawings, sketches, collages, and text. And though many first pages note the joy of opening a new book at the beginning of a trip or project, I’ve never dedicated so much as a page to the sketchbook itself. So this is my paean to the HOLBEIN 33YT-1 MULTI-DRAWING BOOK - OF, 195 mm x 145 mm, landscape format, spiral-bound with brown covers and a brown ribbon tie. There are 28 pages of 80 lbs neutral pH paper (guessing hot pressed): recto has some bite, verso less. Made in Japan.

mode d’emploi

First step is to remove the red plastic label with Japanese characters inserted into the spiral binding. Then open the book to the first facing page and write name with month and year centered about mid-page. Strike a horizontal line a bit wider than name and below that add an address (to which a lost book could be sent).

Between the rear cover and the last page insert a Madonna del Buon Viaggio prayer card from the Tempio di San Biagio in Montepulciano. The same card is transferred from sketchbook to sketchbook. The prayer card dates from my first visit to Montepulciano and offers protection to the traveler, obviously.

Trim the doubtlessly frayed ends of the ribbon ties with very sharp scissors and dip them into a very small quantity of white glue, evenly coating the end. Place the sketchbook at the edge of a table with the ties hanging free allowing the glue to dry.

Check the wire spiral binding to be sure it’s smoothly wound, and that the cut and bent ends are neatly tucked back into the coil. Monitoring the wire spiral is an on-going project and is important to insure that handling the sketchbook doesn’t compromise the pages ability to turn freely.

In order to keep the book tightly closed when traveling avoid the ribbon ties. They’re perfectly fine for the studio, but not so great on the road since, even tied tightly, they allow the pages to slide against one another. Instead place a fat rubber band around the end just inboard of ribbons’ attachment slot. The rubber band should be small enough to hold tight but also fit over your left wrist - its parking place while working in the sketchbook.

If you use the sketchbook as a way of looking then it has to be available and it’s never more available than when it’s already in your hand. Best is to lay the sketchbook into your left hand open palm, spiral binding towards you, bottom edge sitting at your pinky’s first knuckle with your fingers then curling over the bottom. When walking your thumb lays along the back cover, the spiral is to the rear and the cover brushes your left thigh. After a long day of walking it’s nice to rotate the book 90 degrees with the open end down and then slip your fingers inside the rubber band and let the book dangle a bit in your hand.

Packing the sketchbook into a messenger bag or daypack requires some care. To avoid dinging the edges it should never be placed loosely in a large compartment. Ideally it would slide into a pocket or sleeve within the bag that is appropriately sized. It carries best vertically with the spiral binding topside. And it absolutely must be easily retrievable - as in a single move to a reach in and take it out. When traveling the challenge is to capture the immediate impression; having to haul the sketchbook out from somewhere means you’ll just take a foto with your phone. Which is probably even handier.

holding the sketchbook

The source of the greatest pleasure offered by the Holbein 33YT-1 is the way it opens up and finds its place in my hands - book in left, pencil (almost always a pencil) in right. It’s a smooth movement: book carried at arms length then pulled up across the body, right hand grabs the end and flips the book so that the heel of the left is covering the front cover fingers curled around the spiral. Right then slips off the rubber band as the left presses the back cover against your ribs and holds it with pressure from the wrist and underside of the forearm. Your left hand fingers are free now so the right hand slips the rubber band over the left wrist.

Right hand takes the book by the open end and the left slides so that the wire spiral is nestled into the palm’s fold, thumb laying across the cover. Right hand middle finger dives in at the middle and the right thumb then fans the pages to find the new blank one.

Holding the book now simply depends on what you’re drawing. Full landscape mode has the thumb and index pinching the recto with the lower edge of the verso wedged into the joint between the base of the thumb and index. After a while you can rotate your hand so that the spiral binding is laying along your palm which spans the gutter and with all five fingers curled over the top of the page. Hand span is enough to support both recto and verso.

Another option is to lay the box long the full forearm, palm behind, with thumb and pinky hooked over the recto. Maybe my middle finger can get to the end to stabilize but it’s not essential.

When drawing on only either recto or verso it’s best to fold the sketchbook open and back on itself - this is the real attraction of the spiral binding and why keeping it in good shape is key - no gutter and a stable platform. You can hold it either by thumb/pinky combination hooked over top and bottom edges or support the back with the heel and fingers hooked around the end. The book can be rotated hand without any real change in the grip.

You have to stand to draw in the field, drawings done sitting down are always lazy looking. Stand up, feet spread to shoulder width, weight evenly distributed, left elbow tucked into the body if possible. Then the right hand can work.

preferred marking media

Part of living in a sketchbook is eventually finding a way of drawing (and writing) that fits. I love pencils. They’re equal parts crude and highly refined. Crude because who takes a pencil so seriously it can’t be crushed into any number of modes. Refined because they are graded from extremely hard to super soft with each gradient having its own specific qualities. Just as a cellist could speak as much about the bow as the cello, I could write another paean to Faber-Castell SV Castell 9000 H. The H is on the hard side and means my drawings tend to be sharp but also very light - almost impossible to accurately reproduce.

But I also work at times in charcoal, oil pastels, and conte crayons. Once working with one type of tool that approach tends to fill a book. Some books are a mess with colored dust flying and drifting page to page. Or there are smears of oil pastels everywhere. I rarely watercolor or wash, though I like the idea of adding a wash of color once back in the studio. Something about the preciousness of the medium turns me off. Again, once into a rhythm whatever I’m doing will persist for a bunch of pages.

working backwards

The natural flow of work is to keep turning to fresh pages for each drawing but some of the most interesting sketchbooks are those in which I’ve run short of paper and had to work backwards layering drawing on drawings.

paste-ins

I avoid any kind of scrap-booking activity but each book will usually pick up a paste-in of something found or a sketch on loose paper. I’ve sometimes accordioned larger drawings into a book - probably from my days using the Moleskine accordion-fold books. It’s not unusual for yellow trace or portions of plots to get tipped in as well.

inclement weather

If you can be outside you can draw. Use the upper body to shield the sketchbook from rain or snow. If it’s cold out just don’t think about it. If it’s bitterly cold out then draw until you can’t hold the pencil any longer and go find a café to warm up. If it’s hot, draw from the shade.

finishing a sketchbook

Knowing when to terminate the work in a book is an on-going question that gets answered in any number of ways. Easy answer is when the sketchbook runs out of paper, or maybe out of space in the margins and backwards loops. But some books end when the project, trip, or idea is exhausted. And if a book simply sits unattended for too long it should be retired.

using sketchbooks

What is a sketchbook for? (when it’s empty)

When working in the sketchbook I don’t make drawings. I don’t draw drawings. I have a lot of friends and colleagues who make extraordinarily beautiful drawings in their sketchbooks. But the sketchbook is my most important tool as an architect. I use drawing as a way of thinking and/or a way of seeing, as a pry bar to take things apart. It’s dirty messy work and how a drawing looks isn’t even in my mind as I draw. Composition and proportion of the drawing - utterly inconsequential. It’s a place to ask questions. The drawing is just a trace of a process as my eye and brain work together to figure a thing out. Specifically, drawing my way through a building or place is a way of getting that thing into my body so that the experience is a kind of sensory memory. All that matters is the doing of the work in the sketchbooks.

What is a sketchbook for? (once it’s full)

In one sense, as soon as a book is finished its work is done. If the work of drawing is a way of seeing and the drawings themselves essentially a remnant of an inquiry then the sketchbooks aren’t particularly important as things. The buildings and spaces we put into the larger built environment are the point. But the creative and critical work of design is a looping, intuitive, and reflective semi-process and revisiting older projects and field drawings almost always surfaces something new. At especially productive moments the eye and hand can by-pass the brain completely - drawings might include things that never even registered consciously. So re-opening a sketchbook is part of the critical work of re-thinking and re-working.